GIMP is Free and Libre Open Source Software, but none of it is possible without the people who create with and contribute to it. Our project maintainer Jehan was interested in interviewing the volunteers who make GIMP what it is, and sharing their stories so you can learn more about the awesome people behind GIMP!

Early interviews with co-maintainer Michael Natterer and Michael Schumacher were published shortly after the first Wilber Week. Unfortunately, the rest of the interviews from that event have never seen the light of day - until now!

The interview in this article is about Simon Budig, a core GIMP code contributor and advocate. It is especially fitting to share his interview now, as Simon was behind the rewrite of the Path Tool infrastructure that powers the new Vector Layer feature in the upcoming GIMP 3.2.

This interview took place on February 4th, 2017. In addition to Jehan and Simon, Michael Schumacher and Thomas Manni were also involved and asked questions. Thanks also to Alx Sa for transcribing the audio recording after all these years, an ungrateful task but without which we could not publish these!

Jehan: Hello Simon. Can you introduce yourself, in general and in relation to GIMP?

Simon: Hello, I’m Simon Budig, and I’ve been involved in GIMP since 1998 or something like that. A little bit earlier maybe if you count the non-official contributions.

Jehan: What are “non-official” contributions?

Simon: Ah, giving talks about GIMP without being affiliated with the project. But my first patch, I looked it up yesterday, was in April ‘98.

Jehan: What was it?

Simon: It was a fix for the layers dialog regarding the spacing of the widgets. So, you have this box and the spacing between the widgets was basically inconsistent.

Jehan: Okay! I know you’ve worked on a lot of important features in GIMP. Can you share a little about them, like the vector tool?

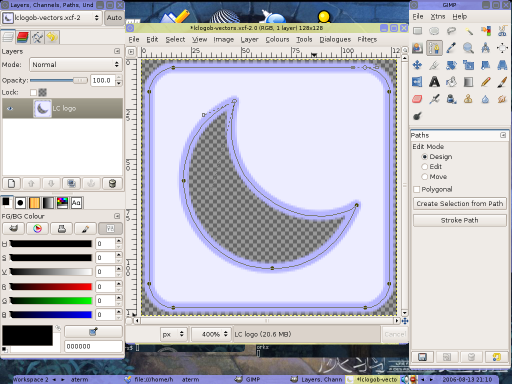

Simon: Yes, I think the vector tool is probably the most important one. It was basically a complete rewrite of the vector tool, getting new infrastructure for vector data, which by the way, is more flexible than we actually use. It’s probably a little bit over-complicated from looking back at the code, and there’s stuff I would do different today – but it works.

Jehan: Could you explain a little more?

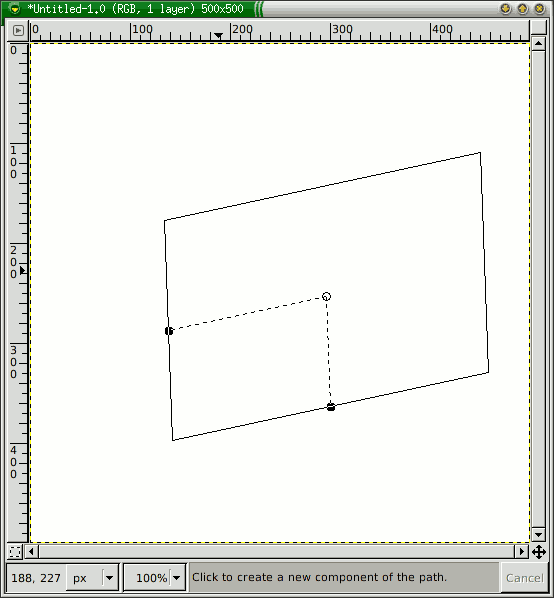

Simon: The vector infrastructure was designed to allow different stroke types. A stroke is putting down the pen, following the path, and releasing the pen. So it was designed to be able to handle different stroke types, but the only stroke type we have now is the Bezier, so you have points connected by Bezier curves and their handles. There’s been a lot of thinking going on about if, for example, you’d like to have rectangle strokes - how would it work to have a rectangle on the canvas? The tool must query where to put the control nodes and the anchor nodes and stuff like this. Ideally, it should be possible to have different kinds [of strokes], but it failed due to UI considerations – how would the user choose what kind of stroke to create? The obvious implementation for a lot of this kind of thing would lead to very unconventional user interactions for manipulating the content – it would be a little bit weird.

[Editors note: Simon clarifies, that he was trying to implement a path tool working within the constraints of the tool infrastructure at that time (2002-2004). He was trying to abstract away from the specific shape to be manipulated. This would have had weird consequences for the user interactions, see for example the screenshot of a prototypical rectangle stroke type above. He at some point scrapped this idea.]

Jehan: It’s quite different from Inkscape‘s SVG vectors. So I guess it’s a different concept from most other software? For instance, if I’m in Inkscape and I make a vector shape I have a concept of a stroke, a fill, and everything. In GIMP you just have a vector that you can stroke separately but it’s not attached to the vector. You can not move the vector for instance and have the fill or stroke follow it.

Simon: Yeah, this basically has to do with what I had to start with. The old vector tool was the same, so it didn’t have fill properties or stroke properties. So, at that point I didn’t see the need to, or I wasn’t confident enough to just throw all of this away and introduce a completely new concept of having objects within the layer stack. This was something that was just over my head. We had a Google Summer of Code project regarding vector layers that was supposed to implement this, but this is something that hasn’t been finished.

[Editor’s note: This work is finally done and you can experiment with a first pre-stable version in development release GIMP 3.1.4. This will be part of the stable release GIMP 3.2.]

And the other thing is that the use of the path tool is quite different than for example in Inkscape. Because Inkscape has a path manipulation tool, which has tons of different buttons and possibilities to do a rectangular select on the nodes and stuff like this, which we don’t have in GIMP. So this would be quite a lot of work to get this aligned to a traditional tool. But on the other hand, what one of the main purposes of the rewrite was to get it more close in this direction because the old path tool was quite different and quite strange.

Jehan: The old tool, that was not by you.

Simon: Right, the old one I threw it away basically.

Jehan: Okay, so what are you working on now? Or do you want to work on something?

Simon: I don’t find the time or energy to work on GIMP as much as I would like, so I’m hesitant with starting bigger projects in GIMP because I’m not sure I can finish them properly. So what I’m mainly doing is lurking around and try to help people there. Yeah. But other than that, my contributions to GIMP are limited and I prefer small-scale things to work on. For example, I’ve been working on the Warp operation in GEGL to make it more similar to what I-Warp has been doing.

Jehan: To what?

Simon: I-Warp [plug-in]. There was a difference in the math which was quite noticeable in some parts and it still has issues. I am not sure if I can resolve this. So I like small, isolated problems.

Jehan: Do you use GIMP?

Simon: I do! But mostly for small scale things like doing diagrams of something. Regarding the use of graphics tools I also like Inkscape a lot. Somehow this whole vector thing triggers the right point in my mind so I like dealing with vectors. But what’s happening right now in GIMP with this GEGL integration and further expansion of the layer nodes is quite interesting as well. So yeah, I like GIMP. Again, I use it for not very artistic stuff but I do use it sometimes. But I’m not the GIMP expert.

Jehan: Your company also does some stuff sometimes, like taking care of stickers.

Simon: Maybe I should explain a little bit. The main work we do in our company is embedded Linux work. We specialize in embedded Linux and we do custom software development for a wide range of embedded devices. Sometimes there’s really crazy things we’re working on. And sometimes in the process of this there’s a use for GIMP. For example, if you create a boot splash and you want to put some basic stuff, some text, some logos together and it needs to be in 320 by 240 and it needs to be 16 bit RGB565 and stuff like this so that the boot loader can handle it – it’s easy [in GIMP].

But a minor part of the company is that we have a history of doing merchandising for a variety of free and open source projects. It’s kind of connected to big events in Germany like the LinuxTag or the – I forgot the name – FrOSCon is one of the conference. So sometimes a colleague of mine has a booth there and sells all kinds of interesting merchandising stuff for different projects. And this is where I help her by preparing designs for the items. For example, if you have some random bitmap and you want to do T-Shirts, the T-Shirts maybe should be silk-screen printed. Then the bitmap is not very suitable because silk-screen printing is done with a low number of very specific colors and you need to create vector shapes. This is something I do with Inkscape for example.

Other things can be done with GIMP, if you do some stuff that is printed digitally you can hand in a bitmap. I’m very much a fan of using the right tool for the job, and this sometimes also means that I invent the right tool for a specific job.

Jehan: As free software?

Simon: They usually get developed to a point where they solve the problem. So, I know how to use them, but nobody else can! For example, I made a tool for one of the LinuxTag T-Shirts. We wanted to have a nebula effect in the background, and silk-screen printing and shades of gray don’t mix well. So I wanted to emulate this by having a very specific dot pattern that kind of relates to the nebula pattern but also is discrete dots printed on the shirts. Not being happy with the bog standard newsprint style patterns, I wrote a Python script to have wavy patterns. So I write a pattern script that generated Postscript output and this Postscript output then got further processed with a mix of various things – it’s been a while since I did this.

[Editor’s note: Simon found one of his old scripts which provided PostScript and Skencil outputs, and shared it with us: dotgenerator.py.]

Jehan: You’ve also shown us various creative stuff you do. So maybe you don’t have a professional artist background, but you do a lot of artistic stuff.

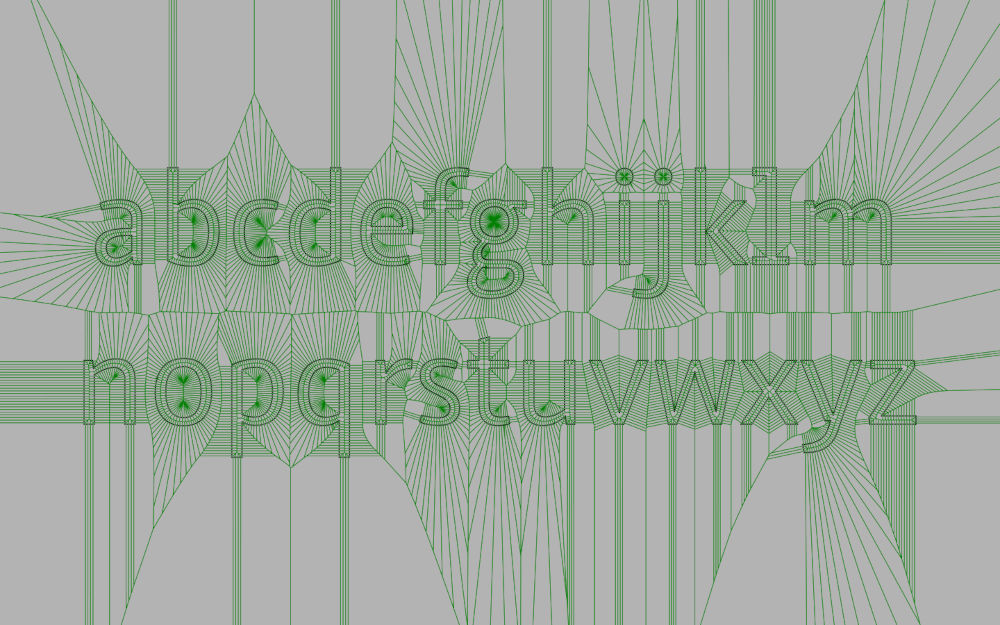

Simon: Yeah this is something I need to get use to, to be confident in calling the stuff I do art. My professional background is actually in mathematics. So I have a diploma in mathematics. Then I kind of got back onto the slippery slope of computer science. And I worked in the CS department of the university, in the algorithm program, so I helped teaching students about algorithms and solving them. But also algorithms with graphics side-effects. For example, one thing I was working on was a tool to visualize an algorithm for creating the Voronoi diagram. I guess I won’t expand on that right now, but the thing is, there is really beautiful stuff that comes out of that. Discovering this is a lot of fun.

Schumaml: Getting back to your involvement with the vector tool, how sophisticated do you think vector editing in GIMP should be? Like should it rival Inkscape?

Simon: Personally I think there are certainly a lot of things that can be improved. One thing that is obvious is vector shapes. Vector shapes would be a big improvement. [Especially] if you have them in a mask, like an oval shape that’s defined as an oval shape and used as a mask. I also think that it would be useful if the vector tool would get revamped a little bit to be more discoverable, because a lot of people are struggling with discovering all the functionality that is there. When I designed this in 2003 or something, I wanted it to be usable for someone who has learned to deal with it. I still think it does this – it’s a little bit doubtful if I fully succeeded with this. It’s a lot better than the tool was before, but other than that – there’s so much functionality in the tool which is hard to present in the user interface. So we have this weird [situation], where there’s lots of key combinations and modifiers that you have to use to get certain functionality and stuff like this. Inkscape solves this by having a tool specific toolbar. But this also means you constantly go back and forth between different tools.

Jehan: So you can have both. It’s discoverable for new people but experts can use the modifiers.

Simon: Maybe that’s kind of the problem. Because I always saw the buttons so I didn’t know about the existence of having modifiers for changing tool functions.

Jehan: I don’t know if Inkscape has this, but in GIMP that could be the solution.

Simon: If Inkscape has that I don’t know, but the toolbar might prevent me from discovering this. So actually in Inkscape it’s quite annoying – when I do vector editing I do it in a very analytic manner because that’s how my mind is wired. So I want to have the nodes and specific shapes and sometimes I do stuff like – for example, you have the elongated oval thing and you want to make it two half circles. So I would have to click here, remove segments, reconnect the points in a different way, so it’s quite a lot of work to do this. I would have to show it.

But yeah, it’s a little bit weird because you need a lot of clicks for seemingly a simple operation. Maybe when you have shapes composed of multiple strokes and you want to change the structure of this, you have to frequently remove the segments between two nodes and then create a new segment between two other nodes, this is quite a lot of mouse work in Inkscape.

Schumaml: Because of the UI?

Simon: Yeah, because the buttons are on the top and I need to decipher the icons again and again because they’re quite similar actually. And I realize it’s a hard problem because it’s not easy to make it clear what is there. But on the other hand they’ve done some improvements recently so more stuff is working as you’d expect it to work.

But yeah, you originally asked where GIMP should go with its vector functionality. I don’t think that it’s necessary to compete with Inkscape regarding this feature. In my personal opinion, we don’t need a spiral tool, we don’t need a star tool, and stuff like this is something where I say “No that’s not necessary”.

It’s useful for Inkscape, artists can do a lot of great stuff with this kind of thing. But then what we should focus on is basically having good integration with Inkscape. So that artwork from Inkscape can be imported into GIMP, maybe not lose all of the information, keeping as much as possible. But then if you look at, for example, the SVG specification that Inkscape is built around, there is a ton of stuff in there! And I don’t think we want all of that.

Jehan: What would be interesting as another feature would be not to build them, but being able to import them and keep them as vector. Like, you implement enough to be able to import them as vectors, even though you could not build them as vectors in GIMP itself.

Simon: Maybe, I don’t know.

Thomas: We have a patch for the vector tool, because there is some bad rendering when you switch on/off the visibility of the active vector.

Simon: Yeah, I haven’t touched the code actually for quite a few years now. In fact the code has changed, it used to be XOR based when I implemented it.

Thomas: X what?

Simon: XOR – like inverting and inverting back. But this is very nice now with Cairo. Regarding the stroke and filling there are some interesting side things, because right now we use Cairo to render strokes and render fillings, and Cairo is 8 bit only which sucks for GEGL.

[Editor’s note: Cairo now has float channel support since version 1.17.2 in 2019, but not yet at time of interview.]

I’m not even sure if they have a specific gamma or if they assume linear.

[Editor’s note: There are also discussions that we replace Cairo for vector rendering with ctx eventually.]

Jehan: Why did you start contributing?

Simon: Why did I start contributing? Because the spacing between the widgets and the layout was inconsistent! (Laughing)

Jehan: Why do you stick around? Will you continue to be a contributor?

Simon: Well, maybe in 20 years, no!

I don’t know, I’m stubborn. And I’m still interested in all of this. I still like what GIMP is doing. I still think my input can help. Well, in the mean time, I did acquire a few additional hobbies, so GIMP has to share my attention with other hobbies.

But I still feel attached to the project, I made a lot of friends there, I like the people. It’s more about the people I guess.

Jehan: Questions, anyone? Maybe we’re finished.

Simon: Well, the food is not there right? It is? Okay, so let’s stop there and if any other questions pop-up we can talk later.

[Editors note: Food arrived at the event. Everybody is distracted by food. 😋]

A few links to know more about this core developer: